Gynecological Anatomy

You may recall learning about the facts of life, but do you remember being taught about your vulvovaginal anatomy? Most women don’t and it certainly didn’t help that body parts below the belly button were often referred to as “down there.” Many women don’t realize that the vulva and vagina are actually separate organs composed of different tissue and that they exhibit different problems. The distinction between the vagina and vulva is comparable to that of the mouth and the lips. If you have chapped lips, you apply lip balm to the surface of your lips and not inside your mouth. The same applies to a vulvar disorder, i.e., you don’t insert medicine into the vagina to treat a condition of the external tissue. On the other hand, if you’re diagnosed with a vaginal disorder, such as a yeast or bacterial infection, you should insert medicine into the vagina.

The vulva is located on the outside of the body.

The vulva is the external part of the female genitalia. It protects a woman’s sexual organs, urinary opening, vestibule and vagina and is the center of much of a woman’s sexual response. (1) The outer and inner ‘lips’ of the vulva are called the labia majora and labia minora. The vestibule surrounds the opening of the vagina, or introitus, and the opening of the urethra, or urethral meatus. The perineum is the area extending from beneath the vulva to the anus.

Diagram reproduced with permission from The Interstitial Cystitis Survival

Guide by Robert Moldwin, MD, New Harbinger Publications, Inc. © 2000.

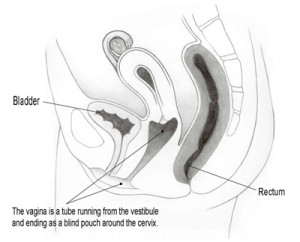

The vagina is located inside of the body.

The vagina is a passageway beginning at the vaginal opening and ending inside the body at the cervix, the lowermost part of the uterus. The urethra sits directly anterior to (in front of) the vagina and the rectum sits directly posterior to (behind) the vagina. The width and length of the vagina vary from woman to woman.

The vagina is composed of a unique tissue that can expand and contract. It serves many functions, such as accommodating the penis during sexual intercourse, expanding to allow childbirth, providing access to examine the cervix and preventing certain harmful bacteria from entering the body. (2)

Courtesy of Dawn Danby

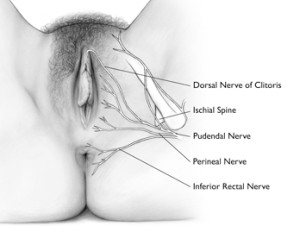

The pudendal nerve transmits pain messages and other sensations from the vulva.

The pudendal nerve originates from the sacral spine, which is located directly below the low back area. The nerve passes through the pelvis and enters the vulvar region near the ischial spine, which is part of the hip bone. From there, it branches off into the inferior rectal nerve, perineal nerve and dorsal nerve of the clitoris. The pudendal nerve is responsible for proper functioning and control of urination, defecation and orgasm in both males and females.

Courtesy of Dawn Danby and Paul Waggoner

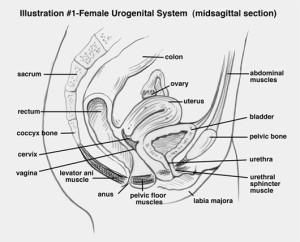

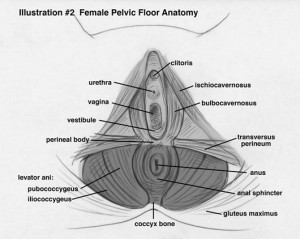

The pelvic floor supports the reproductive organs.

A strong pelvic floor plays a role in trunk stability and mobility, and is critical to overall health. It’s composed of muscles, nerves and different types of tissue that form a sling to support the pelvic organs. The muscles of the pelvic floor work cooperatively to aid in bladder, bowel and sexual function.

As demonstrated in the bottom figure, the pelvic floor is divided into two parts. The lightly shaded, superficial muscles are collectively known as the urogenital triangle. These muscles are the bulbocavernosus, ischiocavernosus, and transverse perineum. The darker-shaded, deep muscles are sometimes called the anal triangle. They include the levator ani, cocccygeus, piriformis and obturator internus muscles.

Diagrams reproduced with permission from

Heal Pelvic Pain by Amy Stein, McGraw-Hill © 2008.